Jeremy O. Harris, Before and After “Slave Play”

When the first coronavirus lockdowns went into effect, and the global mood was a moan of quiet agitation and fear, the playwright Jeremy O. Harris was living in a two-story apartment in London. He had travelled there for a production of his play “Daddy,” about a young Black artist who has fallen under the thrall of an older white man. “Daddy” had débuted, Off Broadway, a year before, and was set to open at the Almeida Theatre at the end of March, 2020; it would have been Harris’s first professional opening overseas. But the show didn’t open, and Harris stayed stranded in London for weeks, then, eventually, for months.

Sad about the play and scared about the world, he passed the first few weeks not writing—although many deadlines, constant companions in his life, hovered at the peripheries of his mind. Since high school, Harris has used the late night and earliest morning as a time to work and party and talk about art with friends; now he binged anime and listened to Fiona Apple and started reading Audre Lorde’s “Sister Outsider,” which he’d always meant to get to. As the weeks wore on, he tired of his vampirism. “I decided that I wanted to see the sun more often,” he said one April morning, as streams of light made bright rectangles on the apartment walls. Waking up at normal hours meant dealing with pedestrian annoyances. He’d begun ordering coffee from a nearby café, and twice in a row, although he ordered it black, it was delivered with milk. “It’s, like, everyone’s watching ‘The Plot Against America,’ ” he said, referring to the HBO miniseries based on the novel by Philip Roth, “and this feels very much like ‘The Plot Against Jeremy.’ ”

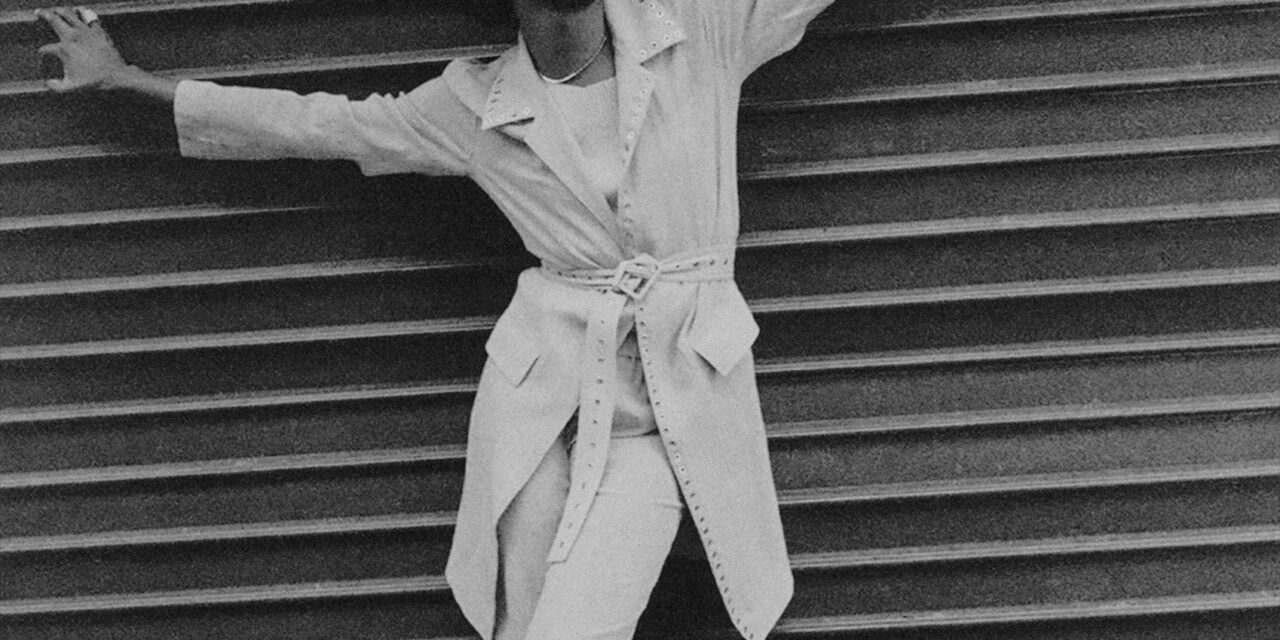

Harris is very tall and very thin, and handles his body with improvised precision, formality within informality, like a dancer on an off day at the mall. A gesture begun in his shoulder always ends at the tips of his fingers. When he gropes for thoughts between sentences, he makes shapes in the air with his hands. He has clear cedar skin and a pert, wide mouth. His eyes are sedate and low-lidded when he’s in a neutral mood, but they open wide when he tells a story or expresses an urgent (often dissenting) opinion. Stories sometimes incite him to stand up and pantomime crucial passages of action. His first dream, before writing, was to act.

When the third coffee came, finally correct, he sat on a couch by a window and lit a cigarette. Lots of people he knew were smoking again, he said, despite the worldwide march of a deadly respiratory disease: “Our lungs could fail us at any moment, and we’re just, like, you know, fuck it.”

Coffee and an American Spirit, white light through the window—his instinct about waking with the sun had been borne out. The apartment was pleasant in the daytime. On one wall was a large abstract painting in russets and burgundies and bright lipstick shades. Upstairs was a bedroom that he shared with his newish boyfriend, Arvand Khosravi, a film and television executive. At the top of the staircase was a glass door leading out to a shallow ledge on the roof, where Harris often went to film TikTok videos—mostly poppy, fast-paced riffs on scenes from classic plays—which he had been posting almost daily. In one, titled “Titus Andronicus Act V,” he lip-synchs dialogue from the TV show “Catfish,” in four different costumes; it’s nine seconds long.

Harris did the TikToks for fun; they were, for weeks, his sole avenue of creative expression. But they were also, not so subtly, a dig at the profession through which he had gained his recent fame. Rooted in the history and the canonical repertoire of theatre, but yoked dramaturgically to hyper-current rhythms and attitudes and styles, the TikToks showed that Harris could do what the big arts institutions couldn’t—keep up. While they floundered, he figured, the show would go on from his phone. He had changed the bio on his frequently updated Twitter account to a kind of epitaph for the theatre: “I spent my 20s devoted to a craft in a coma.”

Stages everywhere were dark; theatre companies and nonprofits were scrambling. In both their public statements and their private conversations with playwrights, they projected blithe optimism, as though their operations would be up and running by summer’s end.

“Like, no, guys!” Harris said, describing his frustration. “We have to reinvent this or re-create this, or else it’s going to be even more detrimental to artists in six months, when you guys have wasted your resources trying to go the normal way.” “Daddy” was still in British limbo, and he had another play, “A Boy’s Company Presents: ‘Tell Me If I’m Hurting You’ ”—his version of a Jacobean revenge drama, based on a particularly bad breakup—scheduled to début in May, at Playwrights Horizons, in New York. Nobody would officially admit—or, perhaps, allow themselves to believe—that the upcoming seasons wouldn’t happen, but Harris was already mourning the new play, just as he was mourning “Daddy.”

His ire notwithstanding, thinking and talking about the failures of his industry seemed to energize him—almost to soothe him—and his online complaints soon came to echo a wider mood. As the initial shock of the pandemic gave way to a reëvaluation of racial and other societal arrangements, Harris became a kind of spokesman for the long-standing and suddenly stark unrest felt by his fellow-artists. It was a moment well suited to Harris’s natural, if somewhat paradoxical, penchant for institutional critique. A happy disrupter of genteel silences, he has nonetheless, however rockily, charted a professional and personal path through some of the entertainment world’s most staid establishment outposts: the Yale School of Drama; Gucci, for which he does modelling; various Hollywood-adjacent neighborhoods in Los Angeles; and now, most visibly, the Great White Way. The previous fall, “Slave Play,” the first of Harris’s works to be staged in New York, had transferred to the Golden Theatre, on Broadway, after an extended run at the venerable New York Theatre Workshop, downtown.

“Slave Play” tells the story of three interracial couples undergoing “antebellum sexual-performance therapy,” in order, presumably, to mend the edges of their relationships, which have been frayed by race. In the first act, before the audience is in on the premise, the couples—dressed in nineteenth-century garb, as masters and slaves—engage in various kinky sexual scenarios calibrated to set off trip wires in race- and sex-sensitive American minds. The second act, in which the actual therapy takes place, is straightforwardly funny. The third is a surreal, largely horrifying duet between one of the couples, a Black woman and her white husband. Over and over, “Slave Play” calls into question the true parameters of sexual consent and tries to wring current-day catharsis from the brutal history of master-slave rape.

In some corners—including this magazine, in a review that I wrote—Harris was lauded for the wild rigor of his vision and the originality of his voice. And the play’s overwhelming success was the precondition for many of the luxuries he now enjoyed: the London flat, the European engagement, a two-year development deal that he had recently signed with HBO. At the same time, “Slave Play” was a kind of troll job, perversely aimed at unsettling and possibly enraging the various constituencies—racial, sexual, institutional, professional—to which he belonged. Harris must have known that the play would have this effect; he seemed to revel in the discursive mess it left in its wake. Even before the pandemic, he had earned a reputation as an enfant terrible, the kind of designation that is made possible only by way of proximity. You’ve got to be fairly close to the big house to even consider throwing stones.

“Something I’ve always wondered is when I’m going to develop the affected-Black-intellectual voice,” Harris said that summer, still stuck in London. He was reflecting on some of his favorite writers and artists of an older generation, and the way that their talk was often as effortfully stylized as their work. He’d been thinking about André Leon Talley, the fashion writer and editor whose high diction and baroque syntax became hallmarks of his style—and seemed, moreover, like a way of asserting his belonging in a largely white milieu. Talley, who died last year, was, like Harris, a tall, queer, highly verbal Black man from the South. His web of complex, sometimes tortured relationships with white co-workers, bosses, and benefactors was consonant with—and had possibly even influenced—the dynamics depicted in “Slave Play.” Harris is unabashed in his study of other artists’ personas. “I’m so interested in personal style, and personal relationships, and class—if not class ascension, then class association,” he said. “Just the lilt of certain people.”

Talk of that voice—I knew what Harris meant without having to ask—got me thinking, perhaps slightly defensively, of my own.

“You have it a little bit,” he said, confirming a fear I’d spoken aloud.

We agreed, though, that the voice of our rough age cohort—Harris is thirty-four—was particular. The sort of Black Millennial writer whom Harris had in mind was not someone who would deploy the suavely concatenated sentences of James Baldwin. Rather, this hypothetical thirtysomething, as eager to showcase pop-cultural with-it-ness and egalitarian humility as to display hard-won verbal acuity, would use locutions peppered with pointed “like”s and “um”s, plus a bit of vocal fry, for subtler tones of falsely self-deprecating color: a Valley Girl with an advanced degree.

“I one hundred per cent know that I have a Valley Girl accent because of ‘Clueless,’ ” Harris said. “But also, partially, I think unconsciously, I did it so that my intellect wouldn’t be intimidating to everyone around me. This is a part of my plays that was also a part of growing up—I’ve always had to figure out how to translate stuff from the academy into language that my mom could understand, without asking her to take time from her life to read, like, Saidiya Hartman.” A dramaturgical note for “Slave Play” quoted both Hartman and Hortense Spillers, another Black feminist scholar, but the play itself takes Rihanna as its primary muse. “I had to bring my learning into a different space of understanding, which is why it’s so much more fun for me to write plays that are based in theory than it is for me to go, ‘And then Jonathan wanted to get a divorce from Becca,’ or things like that.”

Harris speaks in a restless tenor, alternating locomotive bursts with considered pauses; his voice is bright and brackish and warm. He talks about movies and plays and clothes and people’s bodies constantly. His sentences often start with “Have you seen?” or “Have you read?” Unless he already knows, from your work—almost all his friends are artists or public people of one kind or another—that you’ve seen it or read it, and what you think about it, and is prepared to gently argue. He says “yes,” encouragingly but without much emphasis, when he hears something he agrees with, never “yeah.” Two words he uses a lot are “ostensibly” and “psychotic.”

Harris was raised in Martinsville, Virginia, among people who made their livings with their bodies, many of them in factories. His way with words marked him as different. His mother, Veronica Farrish, refused to let family members use baby talk with him. He taught himself to read, and was soon the kind of prematurely unimpressed kid who finds it easier to make friends with teachers than with classmates. When Harris was eight, one of his favorite pastimes, he said, was trading theories with his mother about what had happened to JonBenét Ramsey, the six-year-old pageant contestant whose murder was a tabloid bonanza in the late nineties: “I was, like, ‘O.K., I looked at this document.’ ”

His early interest in true crime briefly convinced him that he wanted to be a lawyer—that standby aspiration for the precociously talkative. But after landing a part in his middle school’s production of “My Fair Lady,” he realized that he possibly just wanted to play a lawyer on TV. Around the same time, Harris was realizing that he was gay, or at least different—this difference was the rare condition for which he didn’t yet have the words. Another discomfort was the unsettled nature of his home life. He didn’t meet his biological father until he was nine or ten; his mother married another man when Harris was four, got divorced when Harris was in middle school, then embarked on another short-lived marriage, to a military man stationed at what was then Fort Bragg, in North Carolina. Harris moved there with his mother and enrolled in a new school. “I was so upset,” he said.

Harris spent much of his childhood in private Christian schools, helped by financial aid. As a result, he became comfortable with the discombobulating tension of being a poor Black kid in a largely rich, white environment. Then, in tenth grade, he got a scholarship to Carlisle, a prep school in Martinsville. In the hallways, there were pictures of each graduating class. As Harris recalls, Black faces didn’t begin showing up in the photographs until the mid-nineties, when the school started a basketball team. “Everybody wanted me to play basketball,” Harris said. “And I was, like, No. I hated that so much. I was, like, I will never do that.” Instead, he took up swimming and dance. He kept up his practice of befriending teachers. “Candace—and Paula, who taught in the middle school,” he recalled, “I would have coffee with them after school, and they were my friends.”

By this point, Harris was determined to be an actor. He got parts in plays and musicals and directed a production of “The Laramie Project,” Moisés Kaufman’s documentary play about the aftermath of the killing of Matthew Shepard, a gay student at the University of Wyoming. His kaffeeklatsch pal Candace Owen-Williams, who taught drama at Carlisle, let him turn an empty trailer behind the school into a black-box theatre, where he and some other friends put on experimental shows. His senior thesis was a one-man production of Wallace Shawn’s “The Fever.”

For college, Harris went to the acting conservatory at DePaul University, in Chicago. The program’s structure was brutal: after freshman year, only half of the students were allowed to continue with the acting cohort; the others were cut, and had to pursue different fields of study if they wished to remain at the school. Harris found the first year—essentially a protracted audition—disorienting. “A lot of my teachers said that my intellect was going to get in the way of me being a real actor,” he said. “I always sort of directed or rewrote the circumstances of the scene to fit the emotional states that I wanted to play around in, to make it more interesting to me.” Part of the problem, he said, was that so many of the roles and scenes were geared toward white actors. But he internalized the message that “if you’re smart, you have to hide it,” he said. “I still stand by all my choices,” he added, “because, in some ways, I made cooler theatre then than I’m making now.” For an exercise in “auto-drama,” he put twenty lamps of different shapes and sizes onstage. The lamps were the only source of light in the show; each one represented a story connected to a father figure. Then, as now, Harris was seeking, and sometimes finding, masked ways to describe the absence left by his actual father. In the glow of each light, he told a version of a memory.

After the first semester, Harris chopped his long hair, nervous about how his teachers might perceive him. When the program made its cuts, the following summer, he called his friend and classmate Erika J. Simpson. Neither had got in. They were quiet for a long time.

It was June—a beautiful month in Chicago but, for Harris, who had just turned nineteen, the grim beginning of an uncertain period. He called one of his teachers to ask why he’d been dismissed; she said that he wouldn’t be “castable” as an actor until his thirties, and rattled off a list of reasons that felt, to him, like “gay-coded shit.” He told me, “There were four Black boys in our year, and the two that got cut were the ones that felt the femme-est.”

He started collecting issues of the Chicago Reader, a free alternative newspaper whose pages he trawled for acting notices. At an audition, he broke down, crying and trembling. He explained himself to the producers—some of them had gone to DePaul; they understood—and they told him that he could step out of the room for a moment, compose himself, and try again. Instead, he just left.

Eventually, Harris got modest parts at small venues in the city. He became an English major, and briefly imagined writing poems. He was interested in the work of Ai, a mixed-race woman from Arizona whose poor upbringing reminded Harris of his own. In her poems, Ai, who died in 2010, inhabited the voices of tough, sly, vulnerable working-class people asserting their dignity—or, at least, some measure of hip and artful defiance—against the backdrop of an indifferent and often hostile world. “You say you want this story / in my own words, / but you won’t tell it my way,” her poem “Interview with a Policeman,” from 1987, begins. Her work would come to influence Harris’s understanding of the possibilities of monologue.

But Harris didn’t remain an English major, or a DePaul student, for long. He dropped out and, a year later, moved to Los Angeles.

By the end of the first pandemic summer, Harris and Khosravi had left the London apartment and were driving around Europe in a car full of their stuff. Khosravi had felt too cooped up in their flat, but Harris refused to move back to the U.S. “This is why it’s hell to date me,” he said. The pair were in Naples, Italy, in mid-October, when Tony nominations were announced, on a live stream. It was evening in Italy; Harris got on FaceTime with his mom, nieces, and nephew, so that he could watch it with them. He had to hop off about four nominations in because the stream that his mom was watching was ahead of his, and she kept screaming before he’d seen the news. In the end, “Slave Play” got twelve nominations, more than any non-musical production had before.

“Slave Play” was a genuinely difficult piece of work, a deliberate provocation. At one post-show Q. & A., a white woman yelled at Harris that she didn’t “want to hear that white people are the fucking problem all the time.” Some Black audience members insisted that the play was oriented toward a “white gaze,” and was a cynical exploitation of the intertwined subjects of slavery and rape. Both currents of backlash were more or less predictable. The dozen nominations seemed to indicate that Harris could start a food fight in the theatre world’s living room and still be invited to sit at its dinner table.

“It emboldens me to be more forthright with my opinions and how I feel about the world, because, if I gave a fuck about what institutions were actually saying to me, the ‘Slave Play’ that got twelve nominations would not be the ‘Slave Play’ that got twelve nominations,” he said. “It would have been a dumber play, and a less complex play, and a less Jeremy play.”

But this institutional approbation also posed a kind of creative challenge. “I think the thing that I’m trying to get over—and I’ve been working on this a lot over the last year—is other people’s excitement about me,” Harris said. “It’s easier for me to write when I’m writing from a place of, like, ‘These people don’t believe in me enough.’ When I have something to prove, I can write so much better.”

Since his time in L.A., if not before, Harris had defined himself in opposition to those around him—or, at least, those with power. He had initially made his way not in professional settings but in the more free-flowing dynamic of late-night scenes. In Chicago, he had begun to understand his personality and physical bearing as a kind of talent. He was funny and gay and six feet five; people gravitated toward him and wanted him to come to their parties. He got a job at a trendy women’s boutique in Wicker Park, AKIRA, where he helped clients find going-out outfits. Often, those clients would invite him to clubs. Soon, he was a night-life fixture.

“I am the No. 1 person who will tell you that I hate gay bars, because I don’t have as much power there,” he told me. “Black and skinny and charismatic—it gives you much more power in a straight bar than in a gay bar. I wasn’t threatening to the straight men there. And I was also a weird honeypot for the night clubs because all these fun girls would want to stick around longer to hang out, and buy more bottles, too.” Night life is a churning economy, only partially visible to most people, a system behind a veil.

He carved out a similar space in L.A., getting a day job where cool and connected people were sure to buy clothes—Barneys this time—and becoming a regular presence in the clubs. He made friends, some of them in show business, and asked around about how to find his way in the industry. Among the people he talked to at parties were important future collaborators: the writer and director Sam Levinson, the filmmaker Janicza Bravo. “I think that my verbal abilities helped me navigate the space,” he said. “And also my style. I have good-to-decent style.”

Harris got small acting gigs: he starred in a short film directed by the actor James Franco; he appeared, very briefly, in the Terrence Malick movie “Song to Song.” But he hated the idea of being at the mercy of gatekeepers, who, like his teachers at DePaul, might label him uncastable. When Lena Dunham’s show “Girls” débuted on HBO, in the spring of 2012, he saw her as a kindred spirit, and a role model. Watching “Girls,” he thought, “This is so perfect, and also I think I could do it.”

Like Dunham—and like Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, of “Broad City,” another inspiration—Harris and Erika Simpson, his friend from DePaul, created a Web series, “#NightStrife,” and uploaded it to YouTube. “It’s two twentysomethings trying to get famous,” Simpson says, by way of explanation, in the first episode. They made only a few episodes, which were not widely seen, though a tongue-in-cheek series promo of sorts, titled “Black Girl Takes a Shit,” has been watched nearly eighty thousand times.

Harris became jaded about Hollywood; he stopped acting, and stopped referring to himself as an actor. He started to call himself a playwright, though he had yet to write a play. He cast about for ideas, unsuccessfully, until he went on a date with a porn star, whose stories yielded the material for Harris’s first play, “Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1,” a kind of fantasia on the theme of online celebrity. With the play—which featured music by Isabella Summers, of Florence and the Machine, another friend he’d made in L.A.—he won a spot at the Samuel French Off-Off Broadway Short Play Festival, in 2014. There, he met a group of young playwrights who are now his contemporaries: Will Arbery, Martyna Majok, Leah Nanako Winkler, Eleanor Burgess.

Afterward, he applied for a fellowship at the MacDowell artists’ residency—and, when he was wait-listed, he called the administration every day until someone told him yes. At MacDowell, he met the playwright Amy Herzog, who encouraged him to apply to Yale. He’d already finished a draft of “Daddy,” and he submitted it to the drama school’s admissions board, along with a heartfelt essay. “The clearest memory I have of my childhood is elegantly staged,” he wrote. “Delicately, it moves in a realm between the cinematic and the theatrical: lights up on an open screen door leading into a wide hallway, my mother (early 30s) downstage paces from one off stage room to another whispering vitriol into a cordless phone, somewhere further off stage we can hear the sounds of a young girl crying, and upstage in profile I sit (12) back to back with a large suitcase looking out of the open door periodically. . . . Suddenly the crying stops replaced by The Pointer Sisters and my mother is standing with my sister in her arms in the middle of the hall tears, a smile and snot dancing on her face, ‘He’s not coming. Come on baby, let’s dance,’ she said. So we did.”

Harris has come to see “Daddy” as a play about furthering his career by seeking the opportunity and resources that an institution like Yale can provide. “Going to Yale was me deciding to marry a white guy on a hill and in order to have the time and space to make my work,” he told one interviewer. Elsewhere, he has described the play as an attempt “to parse the ways I was cradled, coddled and collected by white institutions and how I’ve collected and used them in turn.” He once wrote that he went to Yale with eyes open, “believing that I could take more from this place than they would take from me.”

In early 2021, the demands of Harris’s still fairly young renown finally called him back to New York. Town & Country had planned a multi-page spread to showcase his newly designed home office, which had been furnished by the chic design firm Green River Project. On a cold, pewter-sky morning in January, Harris sat in a studio belonging to Aaron Aujla, one of the firm’s owners, at a nondescript former warehouse in Brooklyn, getting ready to have his picture taken. Someone tended to his hair, always a foremost point of interest in the looks he puts together for magazine covers and red carpets. There were small, feathery tufts of it strewn about the studio’s bright-green floor.

“I think I want just a mustache,” Harris said. He’d come to the shoot with several pictures of the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima at the ready on his phone. He pulled one up: Mishima in his office, behind a desk and flanked by books, pouting fiercely at the camera, his dark brows writhing. The writer’s louche, vaguely sexual gaze did have something of the solitary mustache about it.

Harris has often, with a bit of a wink—and in spite of Mishima’s reactionary politics—called Mishima his favorite writer. A few months earlier, he had tweeted, “Ok guys so to combat seasonal / pandemic depression and the sense that my life moves at a pace my body can’t keep up with I’ve decided to do a workout every day a la my favorite writer YUKIO MISHIMA. Who combatted depression and dread w/ workouts and a failed coup d’état.” In 1970, Mishima and several members of a militia that he had formed attempted to take over a Japanese military base, in the hope of inspiring an overthrow of the country’s constitution. After a fiery speech, Mishima—obsessed with physical beauty and warlike vigor—killed himself with a sword. “Do I hate fascists?” Harris wrote, in another tweet. “Yes. Do I love Mishima? Yes. I’m a Gemini. Two truths can be held.”

Aujla puttered in and out of the studio, smiling and not saying much. He is married to the fashion designer Emily Bode, known for her knit menswear; she and Aujla are neighbors of Harris’s, in Chinatown, and have become his friends. She’d brought a rack of clothes for Harris to choose from. Once in a while, he’d disappear behind a curtain and come out wearing a pair of fluid trousers or a lacy top or a burgundy suit, evocative of Mishima. (He selected the suit as one of his outfits.) When something tickled him, he let his voice rise to a high, smoky giggle. “That’s cunt,” he sometimes said. Between costume changes, he chatted about recent movies, especially a new coming-of-age indie film that everybody seemed to like but that he couldn’t bring himself to watch.

“Arvand hates me for this,” Harris said, referring to his Hollywood-exec boyfriend, “but I can’t stand this kind of shit.” He went on, “It’s always that same thing: ‘Here I am, marginalized little kid—Black, immigrant, gay, whatever—and here’s the wide, wide world.’ ” By now he was acting out the archetype, hunched into a pantomime of childish wonder, his eyes big with fear, his hands clasped. “And now there’s big trouble”—he cowered in terror—“and inner strife”—he anxiously trembled—“but soon”—now he let a smile spread across his face—“I overcome.”

“I knew exactly what that movie was gonna be the moment it started, and I was, like, No, thank you,” he said. Bode, who has a slim face framed by twin curtains of dark hair and speaks in a soft, helpful voice, like that of an expensive therapist, laughed until her face turned pink.

When the shoot was over, Harris took an Uber to Bedford-Stuyvesant to visit the studio of another artist friend, the photographer Matthew Leifheit. Like Harris, Leifheit went to Yale for graduate school and is the entrepreneurial, self-sustaining center of his own career. He edits the magazine MATTE, makes photo books, and teaches workshops across the country. They met because of Harris’s insistence, in New Haven, on spreading his presence far beyond the confines of the drama school: he was known to drop in on photography critique sessions and to speak up, offering references and suggestions. “A lot of people thought he was part of the photo program,” John Pilson, one of the program’s longest-serving faculty members, said. “By the end, we all expected to see him every week.”

Harris had arrived at Yale in 2016. Several of his classmates were far beyond him professionally: they’d had shows produced, they had agents. He was eager to catch up, but soon found himself at odds with the institution. The curriculum was too conservative for his taste; he felt that his instructors were dismissive of his interest in more experimental work. He started taking classes in Black studies and poetry. He also began work on “Slave Play,” which he says “poured out” of him almost whole. He was assigned a faculty adviser, the acclaimed playwright and director Young Jean Lee, who would help shepherd a student production.

Lee is a longtime downtown experimentalist, and many of her work’s subjects—race, class, the body—are also crucial to Harris; he was excited to work with her. But she had extensive notes on “Slave Play,” which Harris mostly declined to take. She objected strongly to the final act, set in the bedroom of a Black woman named Kaneisha and her white British husband, Jim. Their therapy has been a disaster, largely because of Jim’s refusal to go along with goofily degrading role-play. Kaneisha calls Jim a “virus,” and connects their relationship to the brutalities of the past; Jim gets back into character, as a slave master, and gives Kaneisha the abasement she seems to have been asking for.

This sequence, the most hotly debated part of “Slave Play,” stayed in the show, even after the move to Broadway. When Lee saw it in a dress rehearsal, she was horrified; later, she told Harris that it took her more than an hour to calm down enough to give him feedback. The two then exchanged lengthy text messages. “I hope that no one has ever spoken that violently to you about work that so deeply intersects with your being, and if they have I’m sorry,” Harris wrote. Lee replied, “If you’re that irresponsible about putting a rape of a female body onstage, I’m going to call you out on it in no uncertain terms. To turn it around and call me the violent one is a classic move that has been done to me many times, and I’ve never fallen for it, and I’m not falling for it now.”

Their dispute culminated in a formal complaint process, presided over by Tarell Alvin McCraney, who leads the drama school’s playwriting program. Harris used transcripts from those meetings in “Yell: A ‘Documentary’ of My Time Here,” his senior thesis play. I went to see it, in New Haven, in 2019. By then, Harris had already staged “Slave Play” and “Daddy” Off Broadway, but he still had something to prove to his teachers. The most constant formal structure in “Yell” is repeated acts of onstage defecation. Fake shit was everywhere at Yale’s Iseman Theatre that day.

Harris has said that “Yell” was inspired by the radical 1967 essay “The Student as Nigger,” by Jerry Farber, which compares the relationship between American students and their professors to that of slaves and masters. In June, 2020, at the height of the George Floyd protests, Harris shared “Yell” online, and wrote a long accompanying Twitter thread in which he posted screenshots of his text exchange with Lee, who declined to comment for this story. “EVERY DAY THEY TREATED ME LIKE A NIGGA THAT NEEDED TO BE TAMED AND IT MADE ME FEEL CRAZY,” he wrote.

In September, 2021, Harris sat in a chair in a bathroom at a ritzy hotel in New York. The Tonys were finally being awarded that night, and he’d booked a suite nearby, where he could get ready. Also in the bathroom were his hairdresser, Latisha Chong, and a woman tending to his makeup and nails. He sat stock-still, never wincing as Chong pulled through his Afro and started to braid. The three of them, mutually devoted to the task of flashy beauty, calmly chatted about people they knew in common.

“Everybody who knows him thinks he’s gay,” Harris said. “But, I’m telling you, he’s straight.” Both women disbelievingly harrumphed. “Bone straight,” he said.

The bathroom was a center of calm in the otherwise hectic suite. Harris occasionally got up to take a Polaroid of the room—an editor at Vogue had commissioned him to keep a photo diary. Also milling around were two camerapeople shooting footage for a “Slave Play” documentary that Harris had promised to deliver to HBO. They swanned around the room, sometimes going out on the balcony to capture views of downtown and the West Side. Beyond and between the buildings, you could see the Hudson quietly snaking along.

Harris’s assistant kept running out of the room, collecting bouquets of flowers and other gifts that were arriving in a steady stream. Harris had recently interviewed the young gay rapper Lil Nas X for a GQ profile. “Montero—he’s brilliant,” he said, using the rapper’s given name. “The interview felt kind of like a first date.” He asked his assistant to put on a song from Lil Nas X’s new album, a catchy single called “Industry Baby.” “This one is gonna be huge,” Harris said.

Friends continually appeared, at his invitation. His mother and niece were getting their makeup done in a neighboring room. Candace Owen-Williams, his old teacher, was there, too, in a sparkly gown. Harris pointed her out to each new arrival and repeated the story of how she made him feel less alone at school.

This is how Harris relaxes—sitting somewhere near the center of a crowd that he’s convened. Antwaun Sargent, an art critic and a gallerist with Gagosian, walked over to the ledge where Harris’s gold accessories, custom-made for him by the haute-couture house Schiaparelli, sat gleaming. There were chunky rings and cufflinks, a necklace with a pendant made from a cast of Harris’s ear, a “Phantom of the Opera”-style mask modelled after a swooping section of his face.

As the sun began to set and the light in the room darkened, Harris asked everyone to leave so that he could ready himself for the show. That night, in a surprise to prognosticators, “Slave Play” was completely shut out—twelve nominations, nothing to bring home. The next day, the online edition of Page Six carried the headline “Jeremy O. Harris celebrates Tony snubs with two afterparties.”

Early last year, Harris tweeted a casual swipe at the state of television. “I write tv for people who have an intellect for theatre since tv is hollow,” he wrote. “Bc the funny thing is the reason so many filmmakers and theatre makers were asked to make television is bc the medium hit a wall. That’s why almost all the best tv, of late, has been made by exciting practitioners of other forms.”

Stung TV writers and irritated critics noted that Harris now made much of his living from television, and not always in its most rarefied corners. In 2021, he’d done a cameo, as himself, on the reboot of “Gossip Girl.” (The script called for a play within the show, which Harris wrote; later, he got it commissioned by the Public Theatre.) Then he was cast, as a fashion designer, in the second season of “Emily in Paris,” Darren Starr’s critically maligned Netflix series about an American influencer who gets a job in France. The show’s producers told Harris that they were looking for someone reminiscent of a young André Leon Talley.

Sharper observers of Harris’s commentary noticed that he was playing a familiar role. “I support Jeremy O Harris being snotty about TV,” the Times critic Jason Zinoman wrote. “Playwrights used to be like this all the time. It’s a glorious tradition.” The path from New York theatre to a career in Hollywood—where the money and the weather are better, and the audiences are bigger—has been traversed by writers for almost a century. And Harris seemed to be giving television a dose of his usual medicine: let me in and I’ll give you a piece of my mind.

But on his winding path to playwriting, Harris had made the kinds of friends you would make if you were aiming for the screen all along. When Harris was still at Yale, Sam Levinson made him a consultant for his notoriously lurid HBO teen drama “Euphoria.” (Harris is now a producer on the series.) Janicza Bravo got Harris hired as the co-writer for her movie “Zola,” adapted from a riotous series of tweets.

His steadiest Hollywood employment came in the form of the HBO deal that he signed in 2020. The following year, the network announced that he would adapt the novel “The Vanishing Half,” by Brit Bennett, along with the playwright Aziza Barnes, a friend of his. The novel tells the story of twin sisters whose fates diverge: one dissolves into the American mainstream, passing as white; the other anchors herself in Black community. Harris and Barnes assembled a writers’ room to produce a pilot and a “show bible,” outlining the plot of the first season. They led the writers on a research trip to New Orleans, where much of “The Vanishing Half” is set. As the weeks passed, Harris was often airborne, travelling to fashion gigs, conducting interviews for magazines. When he signed the HBO deal, he’d insisted that his contract contain an annual fund for supporting theatre, and he’d used some of that money to create a fellowship for emerging writers. He was always working. He just wasn’t always writing.

Then, the following June, the Daily Beast reported that Harris and Barnes were no longer working on the show. The article cited two sources who claimed that Harris “was let go after having trouble meeting script deadlines.” HBO insisted that he had not been fired. There had simply been creative differences, which were “part of the normal development process.” Harris, HBO added, “is a valued collaborator, and we currently have other projects in development with him.” (He is no longer on an exclusive deal with HBO but continues to work with the network.)

I visited Harris, at his apartment, a couple of weeks later. It was a bright July day, hot in the sun but buoyed by a breeze. He answered the door wearing a long green terry-cloth robe, with dark polish on his fingernails. His young nephew had been wanting to paint his nails and was getting grief about it in his Southern milieu, Harris said, so he had painted his in solidarity. “Sometimes I think people don’t want him to be a ‘punk’ like Uncle Jeremy,” he said.

The Daily Beast hadn’t reported any details about Harris’s approach to the “Vanishing Half” adaptation, but I had heard, from several friends, about a proposed scene in which a lot of feces is flung around. It sounded preposterous but not entirely unlikely. Harris, in his work, likes to explain drastic external action by way of uncomfortable, abject, and often lewd interior depths. His characters earn their brief glories after trudging through lots of shame; his people get splattered.

Harris seemed surprised that I’d heard about the scene in such detail, but was happy to discuss it. He loved Bennett’s book, but wanted to interpret it freely, even radically, something TV writers don’t do enough, he said. One addition he and the writers envisioned was a surrealistic quasi-dream sequence that would send a character’s consciousness “skipping like a stone across the waters of time,” as Harris put it in the show bible. The character would witness a “depraved ritual” meant to cleanse a small town of its communal sins, and the dark bacchanal would include “blackface masks, buffoonery and flying mud and feces.” It would end with “infidelities, thefts and dark family secrets ushered from the shadows into the light.”

Harris was less annoyed by people gossiping about his work than by the suggestion, in the Daily Beast and elsewhere, that he wasn’t a hard worker. “I’m actually really insecure about that,” he said.

He was about to go abroad, and he wanted a new swimsuit for the summer trip; he’d asked Emily Bode to design one for him. We walked to her small tailoring shop in Chinatown, where a board high up on a brownish wall announced the prices for alterations. Half-done garments hung on faceless mannequins.

A tailor silently took Harris’s measurements, then gave him the swimsuit that Bode had left for him to try on: a lime-green one-piece with thin tank-top straps and tight shorts. He had seemed sedate and almost tired in the apartment, but now his mood lifted. He retreated behind a curtain, then came out wearing the suit, hugging his thin body. It fit. He looked into a mirror and spread his arms. He was already smiling.

One night last October, Harris went to the Brooklyn Academy of Music to see the renowned Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove’s adaptation of the novel “A Little Life,” by Hanya Yanagihara. Harris is friendly with Yanagihara—he’d spoken with her about acting in a possible TV adaptation of the book. He attended the play with an old roommate from his Yale days, Michael Breslin, who co-founded the theatre collective Fake Friends. Harris has co-produced two of the collective’s shows: “Circle Jerk,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for drama, and “This American Wife,” a harrowing parody of Bravo’s “Real Housewives” franchise.

“A Little Life” centers on a group of friends in New York, one of whom, a saintly character named Jude, is repeatedly flayed by acts of unspeakable violence. Like “Slave Play,” the novel was dogged by accusations of sadism. After the show, Harris, who has cited the Marquis de Sade as a formative influence, chatted with his friends. They all agreed that some of the show’s most excruciating scenes, which had provoked gasps in the audience, could have been, in keeping with the book, a bit more graphic.

Harris took a car home, stopping for a drink at a bar near his apartment. Writers—a species always overrunning those blocks, which have come to be called Dimes Square—spilled out of restaurants and sidewalk sheds. For a few minutes, cradling his drink, Harris argued amiably with a pop-music critic about the recently released movie “Tár,” which Harris hated.

Back at his apartment, he ate and paced and talked—softly, because a friend, one in a rotating series of medium-term guests, was sleeping in the next room. Soon, Khosravi came home. Like Harris, he is tall and slender and demonstrative; subtle streaks of gray run through the ringlets of his hair. Unlike Harris, he seldom seems excited to argue. Before Khosravi, Harris had a boyfriend who broke up with him in part, Harris says, because of his sudden fame. “Arvand doesn’t mind that I’m a star,” he once told me.

The couple talked for a while about their friends—somebody was drinking too much, somebody wasn’t eating—until Khosravi began to look anxious. They were flying in the morning to a gala in Bentonville, Arkansas, at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Harris didn’t seem stressed.

The next day, at the museum, as Harris wandered a room with paintings by Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, and Kerry James Marshall, Khosravi surprised him by getting on one knee and proposing marriage. He’d had a ring designed by a pair of jewellers who lived across the street from them in London and had become their friends. And he’d asked the playwright Adrienne Kennedy—a hero of Harris’s, and now a frequent e-mail correspondent of his—to write a benediction, to be etched on the inside. It reads, “Happiness. Is. To me. Greatest Thing.” Harris said yes.

A day later, he giddily recounted the proposal on Twitter, adding a pinch of social critique. “But someone, I guess I will?, needs to write about how cringe it is to be proposed to when you haven’t been socialized to be waiting for it,” he wrote. “It’s a really violent trap we set for both parties where you’re asked to be in a play you know the script to and if you deviate from it 💔.”

Harris’s doomsaying in 2020—his sense that the gatekeepers were not doing enough to reimagine and thus preserve the world of theatre—has arguably been validated, in the worst way, in the three years since then. A wave of closures and layoffs has prompted a rash of op-eds about the future of the medium. Harris, as contrarian as ever, is not abandoning the theatre but, rather, becoming something of a gatekeeper himself: he has lately been, almost above all else, a facilitator of other people’s work.

He is currently the presiding playwright for the Yale Drama Series, a role that involves judging the program’s annual prize. After he took the position, last year, he began conceiving a writers’ retreat for some of the prize’s finalists—inspired, in part, by his experience at MacDowell. In March, he announced the inaugural Substratum fellows: four young playwrights who would spend a month at a medieval house, part of the hotel Monteverdi Tuscany, which, along with Gucci, would help cover the expenses.

He was in Italy with the fellows when he got a text from the actress Rachel Brosnahan, who, along with Oscar Isaac, was starring in a revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s 1964 play “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,” at BAM. She hoped he’d come see it. He said he was abroad, and asked if the play might be extended or transferred; she didn’t think so. “I’m going to get you to Broadway,” he replied. He phoned producer friends, and together they engineered a brief transfer to the James Earl Jones Theatre—another play set to open there had seen its financing collapse. The Hansberry revival wouldn’t run long enough to turn a profit, but it would get a wider audience for a work by another of Harris’s playwriting heroes. And the quick transfer suggested a different approach, perhaps, for Broadway: If space opens up, why not take a few chances?

In August, Harris went to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in the Berkshires, to spend two weeks acting in a movie directed by Pete Ohs, who edited the “Slave Play” documentary. Ohs makes largely improvised movies for twenty thousand dollars or less; the tiny budget meant that he could shoot without breaking the rules of the Writers Guild of America strike, which had begun in the spring and showed no signs of ending. The film was a country-house nightmare about contracting disease from deer ticks.

The cast was staying at the house, which belonged to the actress Callie Hernandez, one of Ohs’s collaborators. In the brightness of the afternoon, a wall of trees outside was variously green: dark pine, mild maple, vivid oak. Inside, James Cusati-Moyer, who was in “Slave Play”—his character, a gay man, refuses to describe himself as white—stood at the kitchen counter, mixing flaxseed, honey, psyllium husk, and cranberries in a steel bowl. He was making gluten-free bread, from a TikTok recipe. “You want a kind of cakey texture,” he said. “The woman in the video is incredibly annoying, but the bread is great.”

The movie would begin shooting that night. Harris changed into a white linen caftan and went into town for groceries—he’d volunteered to make dinner, for the second day in a row. He drives with a country boy’s ease; he learned at fourteen, when his mother realized how impossible it would be for her to chauffeur him to all of his activities. He’d already acclimated somewhat to the roads of Great Barrington, and to its local lore. “Birthplace of W. E. B. DuBois,” he said. “They can’t shut up about it—he’s, like, the only Black guy they know.”

Loping through the aisles at the grocery store, he picked up ears of corn with stringy husks and a pack of what he called “white-people aluminum foil,” packaged in a recyclable-looking brown paper box. He’d begun writing a novel about a Black writer beset by deadlines and grief. Harris was very close with his mother’s parents, who have both died in the past few years—his grandfather, Golden, died two weeks before “Slave Play” débuted on Broadway. “Writing isn’t fun,” he said.

At lunch, in a small bakery across the street from a general store, he told me that his cash flow was slowing down as a result of the strike. “The other day, my niece asked me for a new phone, and I had to say no,” he said. “I told her, ‘I’m not trying to be mean—I’m broke.’ ” He pays private-school tuition for her and his nephew; he bought a home, in Virginia, for his mom. He was worried about falling behind on payments.

Back at the house, he enlisted his castmates as sous-chefs—chopping herbs, buttering corn—and began to cook. People were trying on clothes and critiquing the outfits. Would this work for the character? What else did it need? Cusati-Moyer was in a loose crop top. Harris loved it.

“I feel bloated from the bread,” Cusati-Moyer said.

“You are,” Harris said, grinning.

“This is what he was like,” Cusati-Moyer told the others. “He builds you up and then he breaks you back down!”

Harris called his mom to ask her advice on the meal—pork chops, roasted corn, fried apples, all callbacks to his childhood. Should he melt the butter, put the apples in the cast iron, and then pour the sugar in?

“I don’t know if you know this,” he told her, “but there’s a white way to make this, where you don’t just pour sugar.”

“Yeah, well, we make it the Black way,” his mom said. They talked about Harris’s niece, and about the patterns his mom had begun to notice in her romantic life, and about literature. They sounded like siblings who take turns being in control.

She said that she wanted to write a book about her life. “The best way to write is to read really good things,” Harris said. “You have to read this book by a French woman named Annie Ernaux. ‘Happening.’ You’ll really like it.”

He sat in the kitchen, with food in the oven and on the stove, steeling himself quietly for work later on, chatting with his mother. For a moment, his life seemed almost normal. ♦