That time, he was notified via email that his account would no longer be active, and with that, he lost more than 60,000 followers that he had cultivated for over five years.

“All of a sudden, one day, I lost everything,” Morton said.

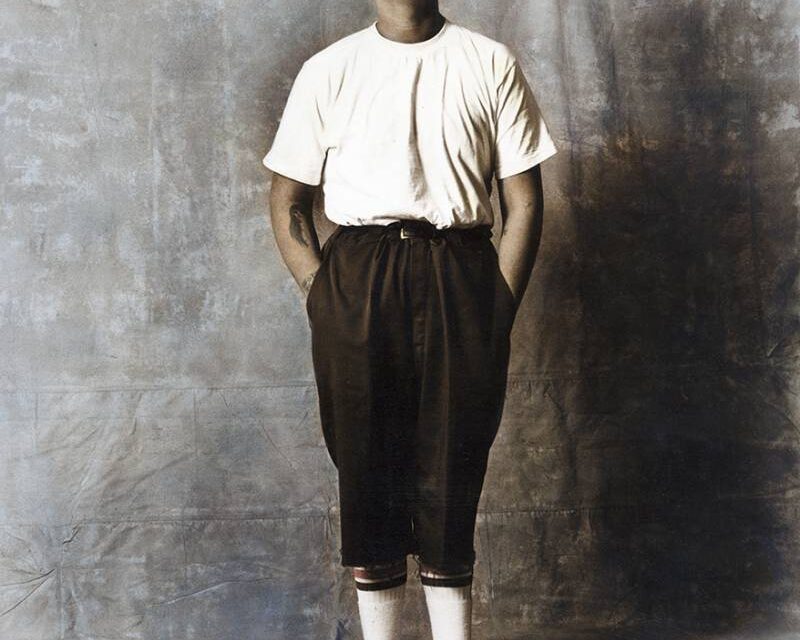

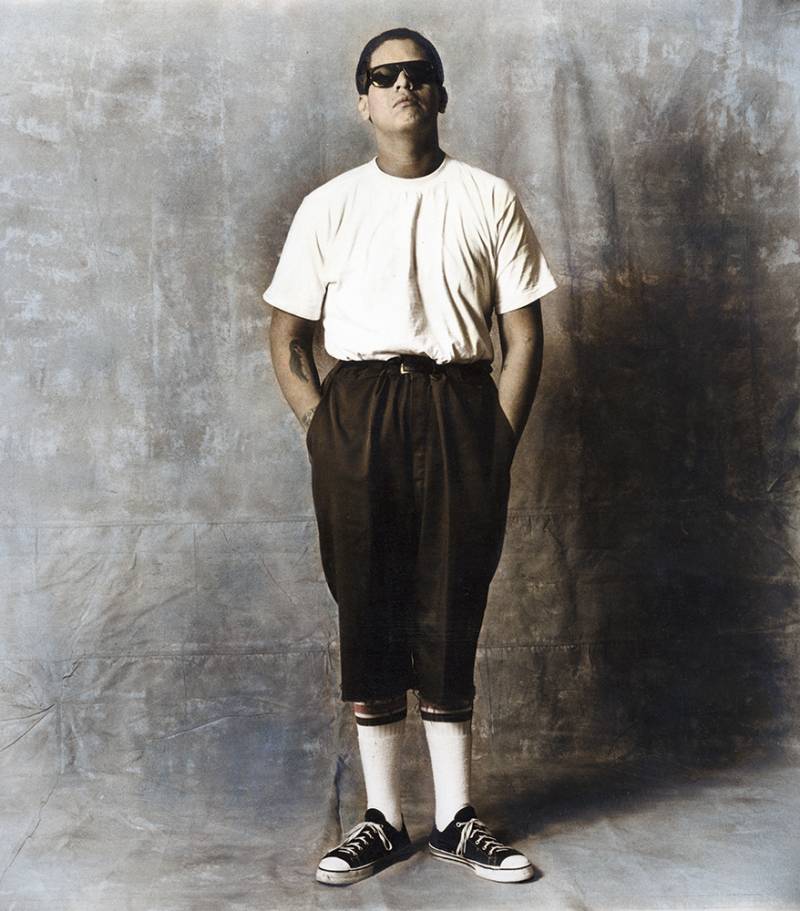

His archive had more than 500 historic photographs, mostly in black and white, that captured images of cholo and African American street culture in Los Angeles.

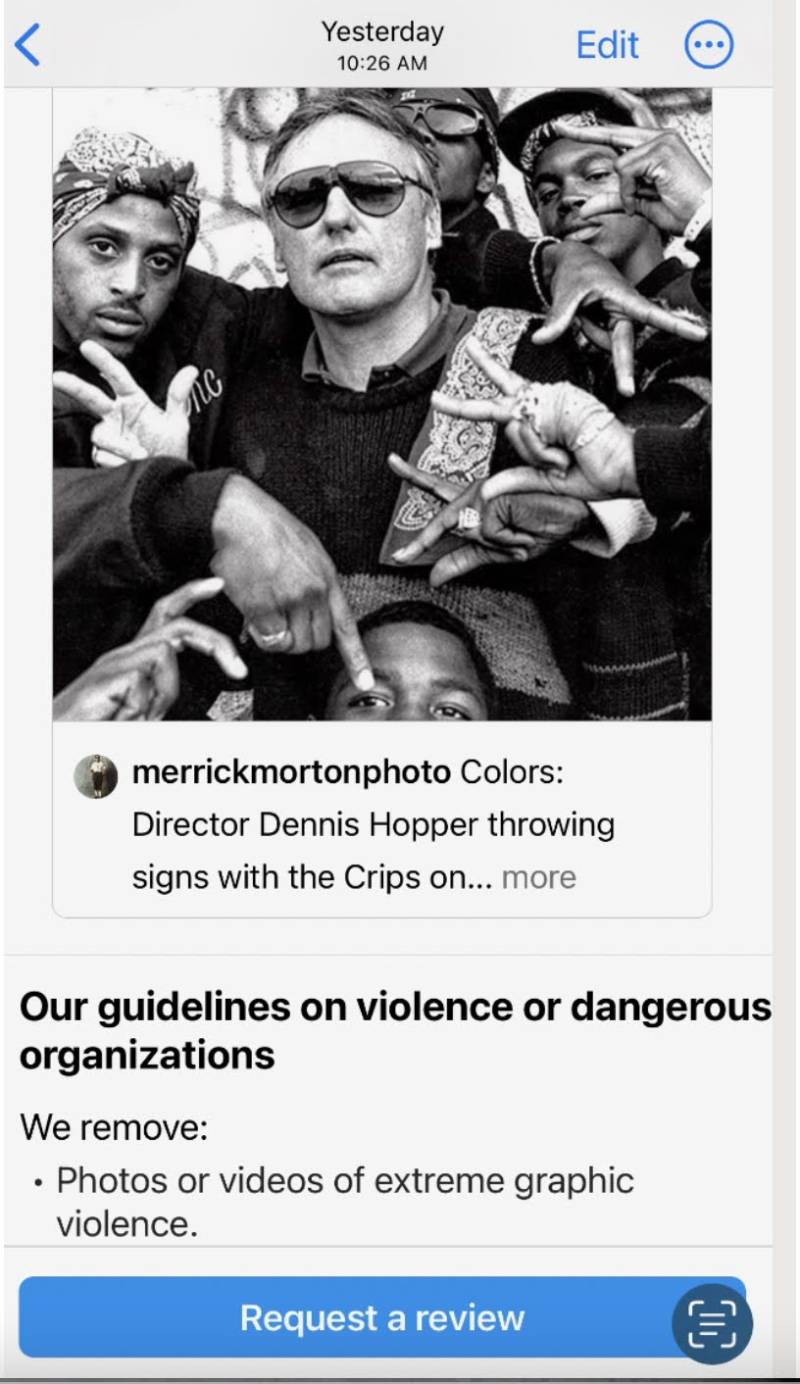

Among the notices Morton received from Instagram, one stated that his photos violated its community guidelines on violence or dangerous organizations. Those guidelines state that Instagram is “… not a place to support or praise, terrorism, organized crime, or hate groups.”

KQED reached out to Meta’s press office multiple times through email to request comment. Meta did not respond in time for publication.

Morton bristles at the idea that his photography belongs in the same category as terrorist organizations and hate groups like white supremacists. He defines his work as “fine art” and says his images have been displayed in many art galleries.

He said it’s also journalism. His work on street gangs has been published internationally. Morton’s goal is that he wants his photographs available to archivists, students, activists and historians. It captures a unique time and place in Southern California that the mainstream media has mostly ignored.

“I think I’m the only photographer in the ’80s who had the cholo culture, who also captured the Black culture and also captured the interactions with the police and these communities,” Morton said.

He’s seen how his photographs provoke discussions about ending the deadly warfare between rival street gangs in Los Angeles. His photos also raise questions about the fraught relationship between the police and the communities they patrol.

But someone — or some machine — has decided these historic snapshots needed to come down, and Morton can’t get an explanation from Meta, Instagram’s parent company. These experiences have left Morton to wonder if the problem stems from the skin tone of the people he features.

Making community and connections

Before Instagram took down his photos, Morton was building relationships with the friends and families of his subjects.

“I had people communicating with me through Instagram. Family members, I was getting back to them,” he said.

A few years ago, he reconnected with Charles “Bear” Spratley whom he met on the set of the 1988 movie Colors. Directed by Dennis Hopper, the film starred Robert Duvall as a Los Angeles Police Department veteran at odds with his rookie partner, Sean Penn, over how to manage their relationships with the Black and cholo street gangs whose territory they patrolled.

on the set of his film ‘Colors.’ This photograph was taken down by Instagram. (Courtesy of Merrick Morton)

Spratley was an active member of the 89 East Coast Crips during filming. Through Morton, he was hired as an extra and received on-screen credit for working in the art department.

A few years ago, Spratley found Morton on Instagram.

“I had been looking for a way to get in touch with whoever was involved in those pictures for years. They were memories for us, you know,” Spratley said.

Once reunited, Morton learned that many of Spratley’s friends, whom Morton had met and photographed for Colors, had died on the streets. According to Spratley, the ones who are still alive have left gang life.

“A lot of these guys, if they made it through living, they are changed. They have changed their lives,” Spratley said.

After attending hundreds of funerals for young men from his community, Spratley founded an organization called B.A.B.Y., or Brothers Against Banging Youth, that works to prevent young people from joining gangs.

Morton, who currently earns a living as a set photographer for film and television, has helped Spratley find union entertainment jobs for young men who have gone through B.A.B.Y.’s programs.

Algorithmic bias in content moderation

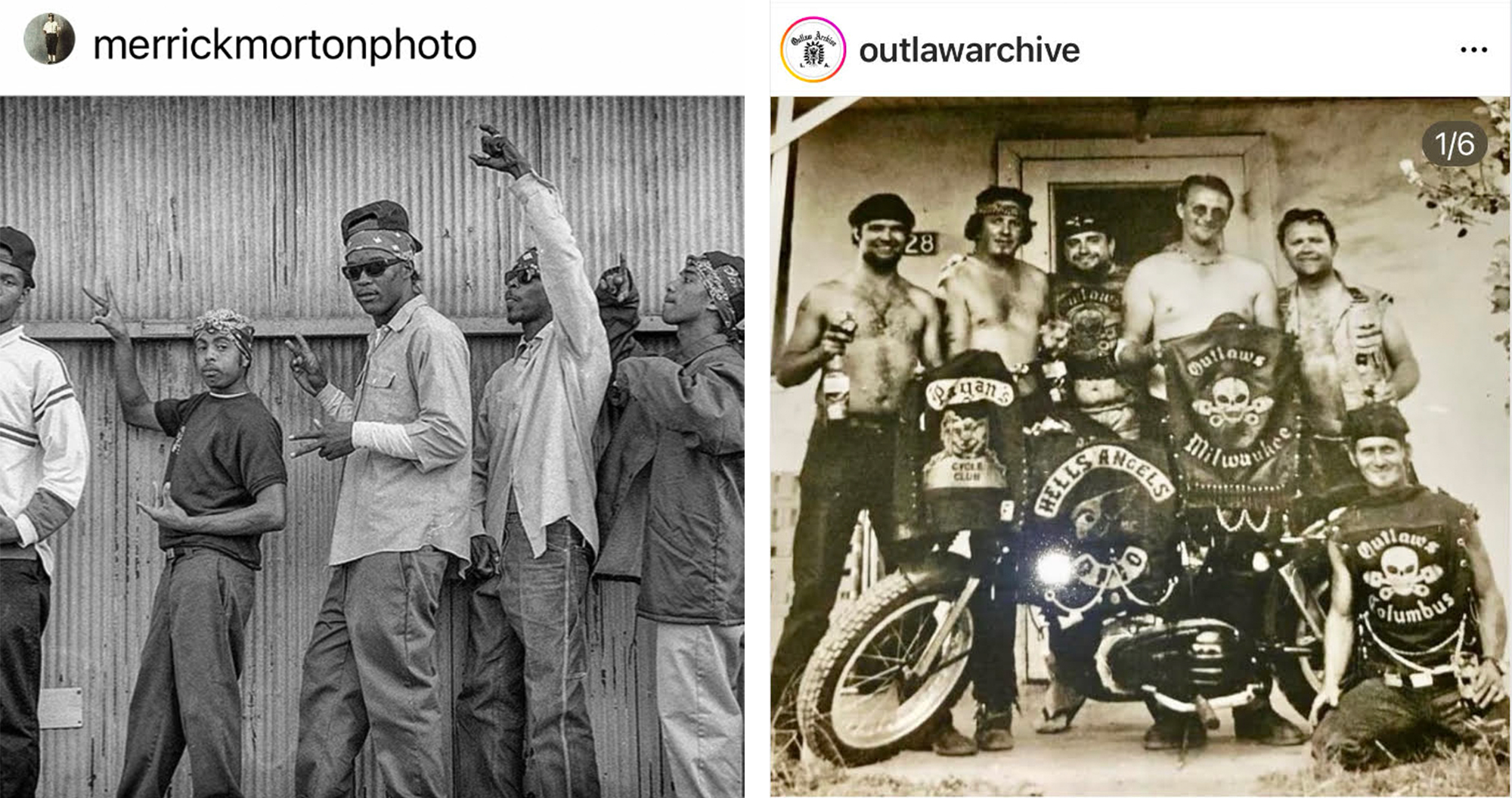

For Morton, Instagram at its best connects people, challenges systems and creates opportunities. But at its worst, it perpetuates social biases against people of color. He suspects his photographs were swept up by artificial intelligence applications because of the skin color of his subjects.

To prove his point, Morton cites this side-by-side comparison: On the left, is a photograph he took that was removed by Instagram. On the right, is a photograph of the Hells Angels, a group that federal law enforcement calls “a criminal threat on six different continents.” The Anti-Defamation League has linked them to white supremacists.

When a machine moderates content, it evaluates text and images as data using an algorithm that has been trained on existing data sets. The process for selecting training data has come under fire as it’s been shown to have racial, gender and other biases.

Joy Buolamwini, a digital activist at the MIT Media Lab, has written that facial analysis software was unable to recognize her until she put on a white mask. She further demonstrated how artificial intelligence had trouble identifying three famous Black women: Oprah Winfrey, Serena Williams and Michelle Obama. Obama, for instance, was identified by artificial intelligence as a young man with a toupee in this video.

Buolamwini argued that “when technology denigrates even these iconic women, it is time to re-examine how these systems are built and who they truly serve.”

The pitfalls of content moderation

Despite his account being permanently banned, Morton believes that if he could get in touch with an actual human being at Instagram, he could explain why his archive should remain accessible to the public.

He did, however, manage to locate someone through his network who knew someone who worked at Instagram, and his original account was restored then. Once his images were back, Morton received a brief apology email from the Facebook Team on behalf of Instagram. (Meta owns and operates Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and more.)